The heads of state were there, all 91 of them, as were dozens of other international “eminent people” including rock stars, supermodels and South Africa’s political elite, all gathered together for a memorial service for Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela that had been described as the biggest farewell to a statesman in recent times.

But the best laid plans, even for such an august occasion, do not always entirely work out. That was indeed the case at the Soweto stadium; one-third of the expected capacity crowd did not turn up, and those who did resoundingly and repeatedly booed South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma, delaying the address that was meant to be the key part of the memorial service.

They cheered to the rafters, however, what emerged as the real keynote speech, that by US President Barack Obama, whose words outclassed every other, even managing to rise above the muffled sound system.

The other winner of the day was the crowd itself which refused to be cowed by the podium into “keeping discipline” and desisting from jeering. While keeping up the pressure on Mr Zuma, they cheered the predecessor he deposed, Thabo Mbeki. There was a warm welcome as well for FW De Klerk, the white president who officially ended apartheid.

The crowd then went on to show that their critical acumen extended to international as well as domestic politics, wildly clapping for Barack Obama and catcalls resounding when George W Bush appeared on the screen above the speakers.

The robust stance of the public present at the stadium stopped the proceedings, as they can do in such circumstances, from sliding into blandness. They were, however, smaller in numbers than expected. Much has been made of the grand scale of the ceremonies around Mr Mandela’s death. As well as the current heads of state, the government was keen to publicise that there were 10 former heads, 86 heads of delegations and 75 “eminent persons” in attendance.

The service was expected to attract a capacity 95,000 at Soweto’s football stadium, the place where Mr Mandela made his last public appearance, at the World Cup finals three years ago. Instead there was a noticeable swathe of empty seats behind the VIP enclosure.

Some blamed the lower turnout on repeated warnings from officials for people to stay away as they could not possibly get in, such was the demand. A large numbers of roads had also been shut off for security reasons; the precautions were, however, haphazardly applied; no searches of any kind were carried out going into the ground through some of the gates.

“It would not rain in Soweto, this day, Madiba’s day”, has been a common refrain in this wet period. But it did, relentlessly, and that appeared to have been the reason some, at least, were put off.

Cyril Ramaphosa, the veteran ANC leader who directed the service, declared: “This is how Nelson Mandela would have wanted to be sent on. When it rains when you are buried it means the gods are welcoming you and the doors of Heaven are most probably open as well.” It was, indeed, a day for Nelson Mandela, and there were plaudits aplenty from the array of international dignitaries in praise of a man who had been raised to an extraordinary level of veneration, a figure who can unite opponents, however briefly.

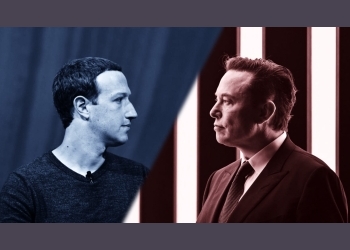

Barack Obama and Raul Castro shook hands, decades-long confrontation and confrontations over sanctions put aside for the moment.

Barack Obama shakes hands with Cuban President Raul Castro (AP)

Barack Obama shakes hands with Cuban President Raul Castro (AP) It was only the second time that a US president had shaken the hand of a Cuban communist leader.

Thirteen years earlier Bill Clinton had done so with Raul’s brother Fidel following a United Nations meeting in New York and, on that occasion, the White House at first flatly denied it had occurred and then charged Mr Castro with carrying out a social ambush for publicity reasons.

On this occasion the two men could unite in their praise for Mr Mandela. The US President called him the “greatest liberator of the 20th century” and compared him to Mahatma Gandhi and Abraham Lincoln. To Raul Castro, who also took to the podium to deliver a tribute, he was a “champion of liberation and equality”, someone who fought for the oppressed “all his life”.

For those in the stands, he was “Madiba” who had freed them from the shackles of apartheid and ensured that his country did not collapse into savage racial war. The promise that the new beginning and democracy offered to South Africa has, in part, remains unfulfilled, leading to unpopularity of the kind scandal-hit Mr Zuma experienced.

Tony Blair was one of three former British prime ministers, along with Gordon Brown and Sir John Major, who had accompanied David Cameron for the trip along with Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband.

Mr Cameron spoke of an “extraordinary scene up there in the heads of state and government lounge” which gave, as well as paying homage to Mr Mandela, the opportunity for practical diplomacy. “A lot of other business will be done, I suspect,” he said.

U2 singer Bono sits next to South African actress Charlize Theron (Getty)

Also present were Bill and Hillary Clinton, François Hollande and his predecessor Nicolas Sarkozy, the singer Bono and the supermodel Naomi Campbell. But the undoubted star of the show was Mr Obama. Introduced to the audience as a “son of the African soil”, as Mr Mandela had been known, he raised the stadium to its feet. “Given the sweep of his life, and the adoration that he so rightly earned, it is tempting then to remember Nelson Mandela as an icon, smiling and serene, detached from the tawdry affairs of lesser men,” said Mr Obama. “But Madiba himself strongly resisted such a lifeless portrait. Instead, he insisted on sharing with us his doubts and fears, his miscalculations along with his victories. ‘I’m not a saint,’ he said, ‘unless you think of a saint as a sinner who keeps on trying.’”

There were glimpses of Mr Mandela’s private life which had not been without controversy. His former wife Winnie, a staunch comrade in the fight against apartheid who later attracted notoriety over political and business activities, seemed distraught as she walked in held by her daughter Zindzi. She embraced Graca Machel, Mr Mandela’s third wife, and spoke quietly before sitting down.

Closing the ceremony, Archbishop Desmond Tutu demanded that the clamour and occasional jeering should stop and he would not give the final blessing until he could “hear a pin drop”. The noise did quiet down briefly after laughter. “Now this is what Nelson would have wanted,” said the cleric.

South African Archbishop and Honorary Elders Desmond Tutu delivers his speech

South African Archbishop and Honorary Elders Desmond Tutu delivers his speech

To 20-year-old Layla Ibrahim, watching from pitchside with plastic sheeting over her to keep out the rain, it was an historical education.

“I was quite young when Madiba and his friends were so active, it is really interesting to see them all here together. The people I am with were a bit embarrassed about the booing of Jacob Zuma because there were so many foreigners present. But I feel people have had to suppress their political feelings in the past and that should not happen any longer.”

Comments (0)

📌 By commenting, you agree to follow these rules. Let’s keep HowweBiz a safe and vibrant place for music lovers!